Fourth wheel and non-musician Fletcher briefly makes himself useful by describing the band. Songwriter Martin Gore disappears, even when he’s on screen. Off-stage, singer Gahan comes across as loutish and arrogant. Prior to the concert footage, the documentary gives insight into some of the on-stage strangeness of the band, and of the group’s internal politics. (Pennebaker is probably best known for his Bob Dylan documentary Don’t Look Back, but it’s his David Bowie concert film Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars that Depeche Mode 101 most resembles) Pennebaker for a documentary on the band and its fans, eventually released, along with an album of the performance, as Depeche Mode 101. The tour culminated in a staggering show at the Rose Bowl, attended by more than 60,000 people. Nine years into their careers Depeche Mode embarked on a grueling 101-show international tour, in support of their album Music For the Masses. Fourth member Andy Fletcher? A non-musician mime that mutely stands on stage, ventrilloquizes, manages the band. Textures layered and melding together, the artificial alongside the organic, hook upon hook weaving through, implying and extending Gore’s harmonic structures. Taking Gore’s chords and melodies and transforming them into a synthetic dance onslaught.

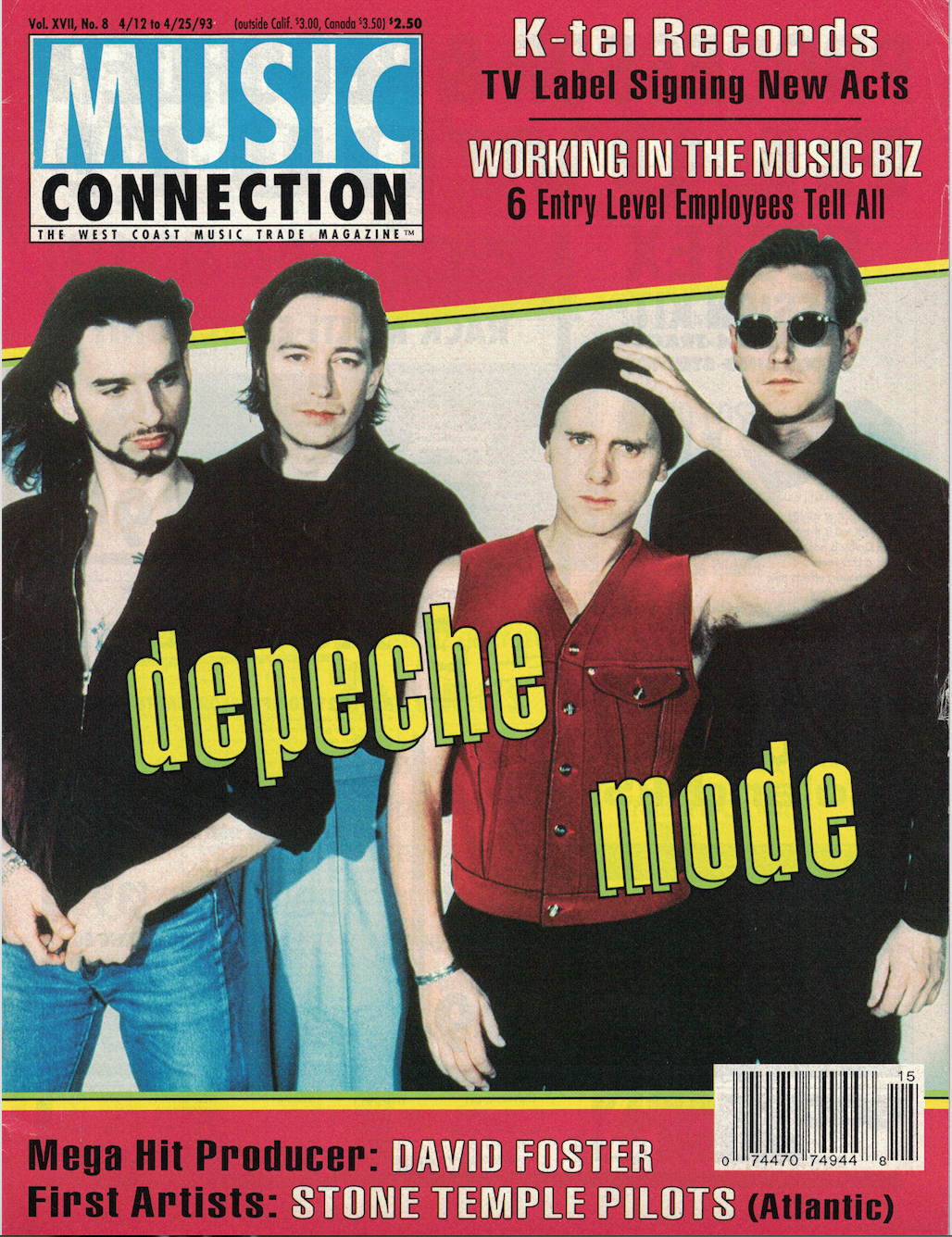

Dave Gahan, the thug, the angel, the unbelievable voice, cold and controlled and icy, somehow vulnerable even in his strength. Martin Gore, the pretty face and the songwriting talent, the man with the melodies and the ideas and the sometimes daft lyrics. Twenty five years ago this month, Depeche Mode was one of the biggest groups on the planet. Having inspired artists across techno, alternative rock, emo and pop, Depeche Mode were inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 2020-the ultimate confirmation of the synthesiser’s enduring influence.As long as I remember who’s wearing the trousers That record established the formula they’ve continued to tweak album after album. 1990’s Violator is widely hailed as their masterpiece: lush, mysterious and multidimensional, pairing some of Depeche Mode’s most compelling songwriting with their most advanced electronic sound design. While their sound remained strictly electronic, Gahan developed the leering voice and louche stage presence of a swaggering rock star (exhibit A: 1989’s bluesy “Personal Jesus”, which Johnny Cash himself would eventually cover). The title of 1987’s Music for the Masses came to look like a premonition: In 1988, they corralled 75,000 fans for a Los Angeles concert-numbers that, just a few years earlier, would have been unheard of for a synth-pop group. Under Gore’s songwriting, key themes emerged: primarily the pleasures of sin and the relief of redemption, with occasional forays into the kinds of dorm-room philosophising (“Blasphemous Rumours”) that have made Depeche Mode perennial faves for generations of brooding teenagers. Their sound grew darker after their comparatively chipper 1981 debut, Speak & Spell, once founding member Vince Clarke left to form Yazoo, then Erasure he was replaced by Alan Wilder, who remained in the band until 1995, leaving original members Martin Gore, Dave Gahan and Andy Fletcher as the group’s long-standing line-up. Depeche Mode proved as much, masterminding an austere yet bewitchingly melodic sound built on cutting-edge synths and clean-lined drum programming. When the UK group got their start in 1980, punk had wiped the slate clean aspiring young musicians were trading guitars for electronics, and everything felt possible.

Electronic pioneers who became arena-filling pop titans, Depeche Mode aren’t just icons of New Wave their early years represent the seismic shift that triggered a tsunami of synthesiser-centred acts.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)